The US and China are currently engaged in the largest rapid vaccination campaigns in human history. A recent Joint Institute-organized roundtable discussion provided opportunity to compare and contrast the progress and the policies governing each effort.

In terms of sheer number of COVID vaccinations administered to date, two countries – the United States and China – lead the pack.

In a little over a month since both countries launched their vaccination campaigns, each has administered more than 20 million doses, far outpacing other nations (the UK comes in a distant third, at just under 8 million doses in the same time period).

The policies and approaches governing these two efforts – the largest rapid vaccination campaigns in history – were the focus of a Jan. 22 virtual seminar organized by the Michigan Medicine-Peking University Health Science Center Joint Institute (JI). The roundtable discussion kicked off a new series of Trusted Conversations, JI-organized events aimed at highlighting and maintaining the U-M Medical School’s largest overseas institutional partnership in a time when COVID-related travel restrictions have strained international academic collaboration.

“We’ve had this really successful Joint Institute. We know right now there’s a lot of press now about the US-China relationships that doesn’t reflect friendships and relationships like ours (between Michigan Medicine and PKUHSC),” said JI Co-Director Joseph Kolars, Senior Associate Dean of Education and Global Initiatives. “We wanted to create a venue that is just for us to share best practices because I think we have a lot to learn from each other.”

The roundtable discussion drew about 60 participants across both Ann Arbor and Beijing to listen to experts from each institution provide an overview of both nations’ respective vaccination strategies.

Progress at Michigan Medicine

For the benefit of the Beijing audience, Michigan Medicine Professor of Internal Medicine Sandro Cinti, who leads Michigan Medicine COVID vaccination task force, provided an national and statewide overview COVID-19 trends to date, as well as Michigan Medicine’s ongoing vaccination campaign.

As of Jan. 21, Michigan Medicine had administered about 30,000 vaccine doses. The system has the potential capacity to vaccinate as many as 4,000 people a day, Cinti reported, but there are two challenges in reaching that figure. The first is vaccine availability, which hasn’t been entirely consistent. The second is a personnel issue.

“We’re having difficulty finding vaccinators – people who can give the vaccine,” he said. “Many of our physicians have rolled up their sleeves to help. And people are coming out of retirement to give the vaccine.”

The vaccination campaign is scaling up at a time when Michigan’s overall COVID case numbers are trending downward, good news that is tempered by the recent identification of a new, more virulent strain of COVID-19 in the state.

“Right now in Michigan, things are looking better. Our hospitals aren’t as full,” Cinti said. “But recently we’ve seen our first cases of this variant strain of COVID, a new virus that spread 50% more rapidly than the previous one. That’s big concern that we’ll be dealing with.”

Progress in China

From Peking University, Health Economist Professor Hai Fang outlined China’s national vaccination strategy. While similar overall – China too is prioritizing essential workers in healthcare and other sectors, followed by the elderly and those with comorbidities that make them high-risk – the approach is not identical.

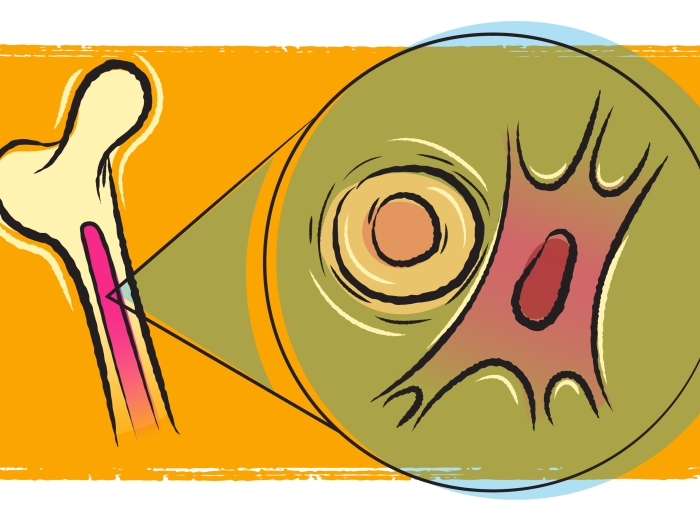

Unlike the United States’ RNA-based vaccinations, China is relying on traditional vaccine technology using inactive virus. Four vaccines have been authorized in China for emergency use, with more in the pipeline. The country’s short-term aim is to vaccinate 50 million primarily high-risk citizens ahead the mid-February Chinese New Year Holiday, when many are expected to travel.

Longer term, Chinese leaders plan to have enough vaccine to inoculate the entire eligible population – 1.3 billion people – by the end of 2021. (Some of Chinese vaccines are for approved patients as young as 3, and inoculating children is part of China’s strategy.) China’s vaccines also require two doses. The country has established about 925,000 vaccination sites in hospitals and clinics but also facilities like stadiums and museums, Fang said.

But the country has a long way to go. According to the international tracking database at Our World in Data, China to date has administered about 1.6 vaccine doses for every 100 of its citizens, compared to about 9 per 100 in the United States.

“This is the first time in China’s history that so many people will be vaccinated in a very short period,” Fang said. “The Chinese government has announced that all these vaccinations will be free.”

Success and setbacks

Ironically, some China’s vaccination rollout challenges result from the fact that the country did such a thorough job of controlling the spread of COVID-19 early on. China has reported less than 50,000 new COVID-19 cases since March 2020, compared to the United States’ 26 million cases.

By summer, when Chinese drug makers were ready to begin large-scale clinical trials of potential vaccines, there simply weren’t enough COVID cases in China to run effective experiments at scale. They had to organize the trials elsewhere, in places like Brazil, Morocco, and the United Arab Emirates.

The result is that their vaccine efficacy data is derived from primarily non-Chinese populations.

“For the phase one a two, the trials were conducted in China. The problem is after the middle of last year, there were very few infections,” Fang said. “The Chinese government had no choice but to conduct the phase three trials in other countries.”

That wasn’t the only unintended consequence of China’s COVID-19 mitigation effort; China’s early success that curtailing the virus’ spread also effectively suppressed public desire for vaccinations. Surveyed in March 2020, in the aftermath of the Wuhan lockdown, more than 50 percent of respondents indicated a desire for a vaccine ‘as soon as possible.’ In a similar survey conducted in November and December, that figure fell to 25 percent.

“One of the chief reasons is that by November there are very few infections in China. People may not want to rush in a to get a vaccination so quickly,” Fang said. “That decline in willingness to get the vaccine as soon as possible is a challenge for the Chinese government to reach herd immunity.”

The different issues faced by each country, many stemming from the vastly different initial mitigation efforts, is striking, Kolars said.

“The hardest thing for me to hear is how low the rates are right now in China,” he said. “In the US, we’re at war with COVID. It is such a problem for us and I think we have a lot of things to learn in terms of process and ways forward,” Kolars said.