5:00 AM

Author |

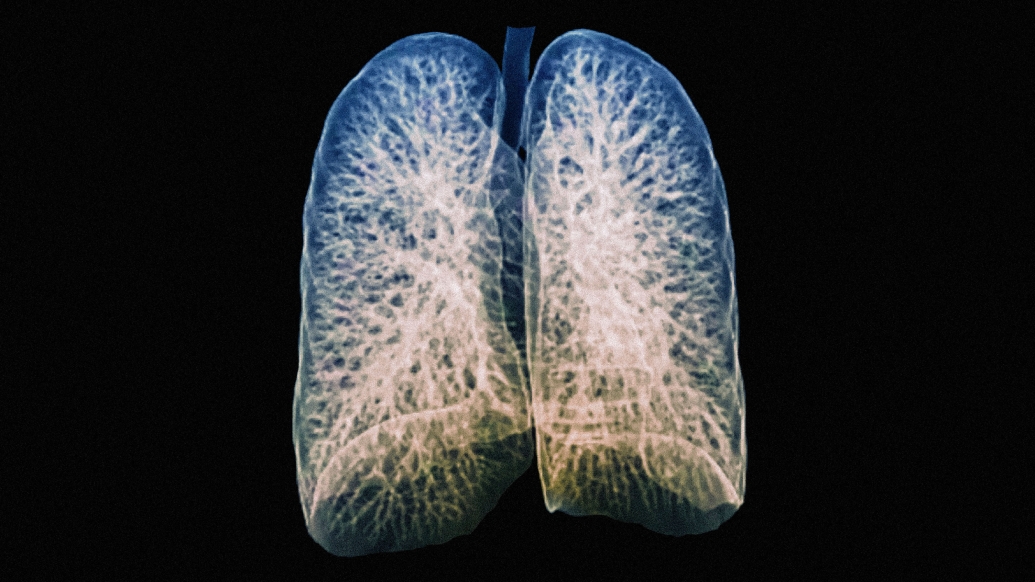

The most common type of lung fibrosis — scarring of the lungs -- is idiopathic, meaning of unknown cause.

Researchers are urgently trying to find ways to prevent or slow idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and related lung conditions, which can cause worsening shortness of breath, dry cough, and extreme fatigue. Average survival following diagnosis of IPF is just three to five years, and the disease has no cure.

A recent U-M study from a team led by Sean Fortier, M.D. and Marc Peters-Golden, M.D. of the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at U-M Medical School uncovers a pathway used during normal wound healing that has the potential to reverse IPF.

Lung scarring

Using a mouse model, they simulated IPF by administering bleomycin, a chemotherapy agent that causes cell injury and confirmed that the resulting lung scarring resolved itself over the span of about six weeks.

Because of this, “studying fibrosis is kind of tough,” said Fortier. “If we’re going to give experimental drugs to try and resolve fibrosis, we have to do it before it resolves on its own.

Otherwise, we will not be able to tell if the resolution was the action of the drug or natural repair mechanisms of the body.”

However, he said, “there’s actually a lot to learn about how the mouse gets better on its own. If we can learn the molecular mechanisms by which this occurs, we may uncover new targets for IPF.”

Fibroblast cells

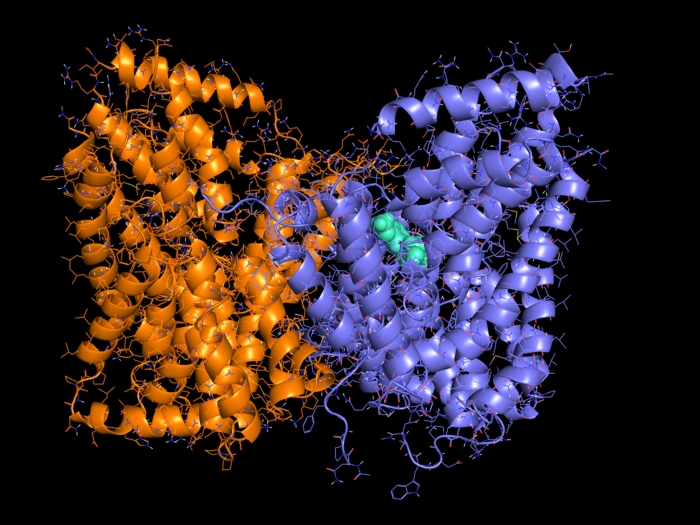

The process by which lung injury either leads to healing or fibrosis relies in part on what happens to a cell called a fibroblast, which forms connective tissue.

During injury or illness, fibroblasts are activated, becoming myofibroblasts that form scar tissue by secreting collagen. When the job is done, these fibroblasts must be deactivated, or de-differentiated, to go back to their quiet state or undergo programmed cell death and be cleared.

“This is the major distinction between normal wound healing and fibrosis – the persistence of activated myofibroblasts,” explained Fortier. That deactivation is controlled by molecular brakes. The study examined one of these brakes, called MKP1 – which the team found was expressed at lower levels in fibroblasts from patients with IPF.

By genetically eliminating MKP1 in fibroblasts of mice after establishing lung injury, the team saw that fibrosis continued uncontrolled.

“Instead of at day 63, seeing that nice resolution, you still see fibrosis,” said Fortier.

“We argued by contradiction: when you knock out this brake, fibrosis that would otherwise naturally disappear, persists and therefore MKP1 is necessary for spontaneous resolution of fibrosis.”

CRISPR techniques

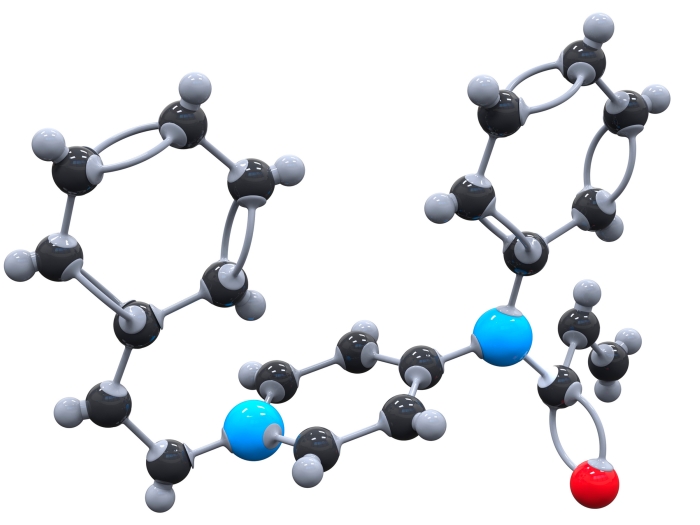

They performed several additional studies using CRISPR techniques to demonstrate how MKP1 applies the brakes, mainly by deactivating the enzyme p38α, which is implicated in a cell’s reaction to stress.

Furthermore, they demonstrated that neither of the two current FDA approved drugs for lung fibrosis, pirfenidone and nintedanib, are able to turn off myofibroblasts.

“That’s totally in keeping with the fact that they do slow the progression, but they don’t halt or reverse disease,” said Fortier.

Fortier hopes the discovery that this pathway reverses fibrosis leads to exploration of additional brakes on fibrosis.

“So much work on fibrosis has focused on how we can prevent it, but when a patient presents to my clinic with a dry cough, shortness of breath, and low oxygen as a result of underlying IPF, the scarring is already present. Of course, we’d love a way to prevent the scarring from getting worse, but the Holy Grail is to reverse it.”

Additional authors: Natalie Walker, Loka R. Penke, Jared Baas, Qinxue Shen, Jennifer Speth, Steven K. Huang, Rachel L. Zemans, and Anton M. Bennett

Citation: “MAP kinase phosphatase-1 inhibition of p38α within lung myofibroblasts is essential for spontaneous fibrosis resolution,” Journal of Clinical Investigation. DOI: 10.1172/JCI172826

Sign up for Health Lab newsletters today. Get medical tips from top experts and learn about new scientific discoveries every week by subscribing to Health Lab’s two newsletters, Health & Wellness and Research & Innovation.

Sign up for the Health Lab Podcast: Add us on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or wherever you get you listen to your favorite shows.

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!