In a world where 50% of people who undergo lung transplants live about 6 years after their surgeries, Mary Pierce is a rarity.

5:00 AM

Author |

Mary Pierce still remembers the first deep breath she took after her lung transplant.

For so many years, she hadn’t been able to fill her lungs with air. While eating, she had to take breaks to breathe. She couldn’t ride her motorcycle anymore because she couldn’t take in enough oxygen with the shield on her helmet closed.

But after her successful double lung transplant at the University of Michigan Transplant Center, she could finally inhale fully again.

“I said, ‘If this is the only good breath I get, I’ll be a happy camper,’” Mary Pierce said. “Now it’s 30 years later. I didn’t expect to live this long.”

That’s because 50% of people who undergo lung transplants live about six years after their procedures given their susceptibility to infection. That number has barely budged since Mary Pierce’s transplant on April 3, 1993.

Yet Mary Pierce, now 76, is one of a small group of patients who have far outlived expectations. Among the medical community, there’s not a definitive answer as to why these patients do so much better than others.

For Mary Pierce, they say, it was likely a combination of factors.

Her diagnosis of the rare disease alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, which, despite often causing significant lung problems, has decent survival rates after transplant.

The fact that she received a double lung transplant instead of a single one, a rarity at the time.

Her high-quality medical care. Her commitment to diet and exercise. The purpose she found in raising awareness around alpha-1 and transplantation by riding her bike across the country and in competitions like the World Transplant Games, where she won a gold medal in 1995.

“She’s dauntless,” said Mary Pierce’s husband, Todd Pierce. “If there’s a problem, let’s get at it — over, around, under or through. That’s her orientation to any problem she comes across.”

And ultimately, she was probably a bit lucky.

“A good portion of survival is the medical care we get,” Mary Pierce said. “A good portion is what we as the patients put into it. The rest of it is pure luck.”

“There was some hope”

Mary Pierce’s shortness of breath started in the early ‘80s, when she was in her 30s.

Initially, she attributed the problems to her habit of smoking and blamed herself for her declining health.

But when she eventually sought out medical advice, Anthony Salvagione, M.D., an internal medicine physician in her hometown of St. Joseph, Michigan, suspected that something else might be going on. He tested Mary Pierce for alpha-1, an inherited disorder that can lead to permanent lung damage known as emphysema.

The doctor called her on her 40th birthday to share the news. Yes, she did have alpha-1 and severe emphysema. But, he says, the FDA had just approved a medication to slow down the progression of the disease, and hospitals in the United States were starting to do lung transplants.

“There was some hope,” she said.

Mary Pierce had recently become a vice president at a large manufacturing company, but now she went on disability and spent her time in the libraries of colleges and medical schools to read up on alpha-1, lung disease and transplantation.

She came up with an exercise program for herself and worked with researchers in New Jersey to get the nutrition she needed, infused through a port implanted in her shoulder. Her weight had fallen to 99 pounds, and she was burning 2,500 calories just to get through the day, so an innovative, high-fat diet helped her return to a more stable weight.

Once she was more stable, her local doctor recommended meeting with the health care providers at U-M to see if she’d be a good candidate for a lung transplant.

She and Todd Pierce both remember the first thing a U-M doctor said to them: No double lungs.

At the time, donor lungs were in such short supply for transplants that it was considered controversial to give one patient two of them.

“Half a lung would have been fine with us,” Todd Pierce said. “Whatever you can pass out, anything to make it better.”

Mary Pierce was put on the transplant waitlist in late 1992. She figured she might have to wait a long time given the scarcity of organs and the number of people who needed them.

But, on April 3, 1993, she woke up sweating with tears running down her cheeks. She’s had “this little thread of a dream” in which her late mother gave her a hug and then pushed her away, “as if I had something important to do,” she remembered.

Later that evening, while she was watching Star Trek with her son, the call came that a lung was waiting for her.

Mary Pierce put down the phone and sat silent for a few minutes. She knew that as soon as she told her husband, “all hell was going to break loose.”

“He was going to throw me in the car and make me run,” she said. “I wanted to celebrate for a bit.”

She was right. Todd Pierce couldn’t figure out why she was dawdling. At one point, after she had taken a while to choose clothing to bring with her, Todd Pierce threw everything from her closet — purses, belts, hats — into large trash bags and tossed them in the car.

“He figured if he took everything in my closet, I would get my ass in gear,” Mary Pierce chortled.

“All she had to do was walk bare naked through the front door of the hospital,” Todd Pierce said. “Everything else would be taken care of.”

“We were groundbreakers”

He was right. U-M was prepared for these types of moments, despite the fact that, by 1993, the health system had only been performing lung transplants for three years.

Lung transplantation was still a relatively new phenomenon, beginning well after major medical centers introduced kidney and heart transplants in the United States.

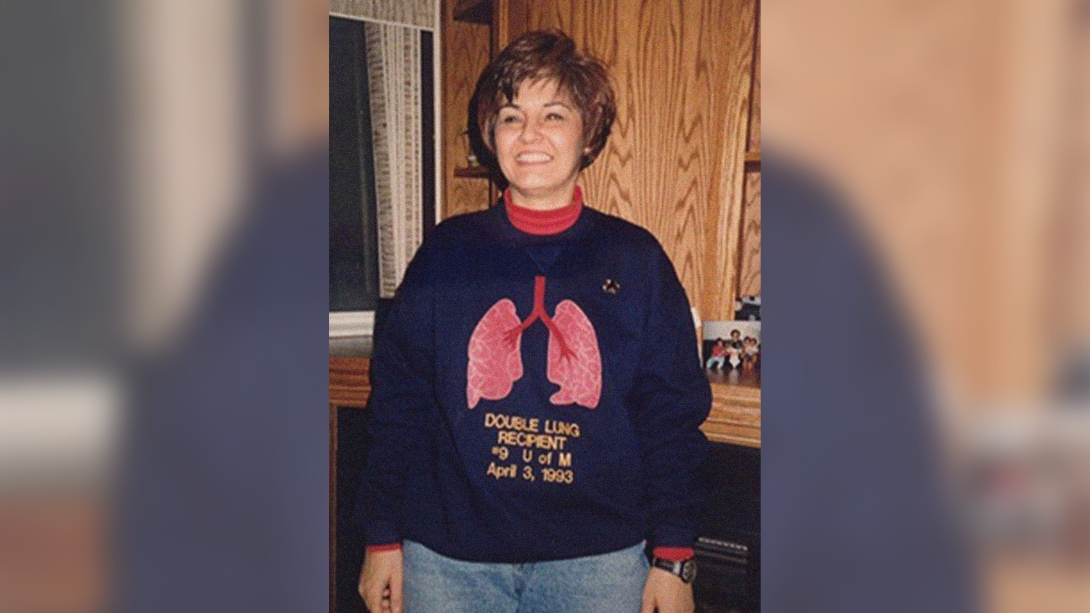

Mary Pierce wearing a special sweatshirt from a lung transplant friend. “This sweatshirt gave me the courage to go ahead with the surgery.”

G. Michael Deeb, M.D., an associate professor of surgery at U-M at the time, had founded U-M’s lung transplant program alongside Joseph Lynch III, M.D., now the Holt and Jo Hickman Endowed Chair in Advanced Lung Disease and Lung Transplantation at UCLA Health.

Deeb and his team spent many afternoons in the large animal lab, practicing lung transplants on sheep.

They ran simulation drills for catastrophes that could happen. They figured out how to limit the amount of time when blood wasn’t flowing through the lungs they transplanted.

They didn’t know the best suture techniques for lung transplants, but because Deeb had particular expertise in heart surgery, he used a certain type of stitch and material that was common in cardiac procedures.

It turned out to produce lower complication rates than other transplant centers were seeing.

“We were groundbreakers,” said Deeb, now the Herbert Sloan Collegiate Professor of Cardiac Surgery and an internationally renowned expert in cardiac surgery. “We were out there taking risks and stepping into the unknown. But these weren’t just random risks — they were well calculated. We did our homework and we studied, and we practiced. We were as prepared as we could be or any other place was or could be, and a lot of that preparation and teamwork was what made us successful.”

The planning certainly made it easier for the team to pivot when challenges arose. For instance, Deeb and co. had intended to give Mary Pierce just one lung from the donor and transplant the second lung into a different patient. But they quickly realized the other patient was too fragile to survive a surgery.

So Mary Pierce received both lungs, undergoing just the ninth double lung transplant in U-M’s history.

Todd Pierce remembers seeing Deeb get off the elevator the morning after the transplant. He thought the 14- to 16-hour surgery might have gone poorly because Deeb looked so exhausted.

But no, the news was good. Mary Pierce didn’t experience any acute rejection, when the body’s immune system tries to attack the donated lung tissue.

“From that point on, it was pretty much a joy ride,” Todd Pierce said.

“The whole situation turned out to be my good fortune,” Mary Pierce said.

As time went on, transplant centers would realize that people with alpha-1 and others with emphysema have good survival rates after lung transplantation compared to some of their transplant peers — but that they don’t fare as well with single lung transplants as with double.

Mary Pierce’s success gave U-M an early indicator of that pattern.

“She was the reason we started doing double lungs,” Deeb said. “After she did extremely well, we started doing double lungs in everybody, and our outcomes were superb. We were the highest in the nation at the time.”

In general, double lung transplants provide a variety of benefits, including a larger amount of healthy tissue to draw on in case of infection or scarring. Yet single lung transplants are often still preferred for those who are older, in severe need of a transplant or, as the original argument held, to extend the donor organ supply to help more people.

“I think the increase in double lung transplants has prolonged the survival of patients,” said Kevin Chan, M.D., the department of internal medicine vice chair of clinical experience and quality at U-M Health, the previous medical director of lung transplantation for the U-M Health Transplant Center and Mary Pierce’s current pulmonologist. “But there are still that that we would prefer to do singles due to survival equality based on specific pre-transplant diagnoses, very severe illness with the inability to wait for two lungs and because the organs can be offered to more people, right? So, you have to decide between greater good or individual good, quality of life or just survival. These are tough decisions made together with the patient.”

“The most important thing I had done”

Mary Pierce didn’t wait long to make use of her new lungs. Although Todd Pierce had barricaded her motorcycle amid bandsaws and car parts in the garage, she trotted out her bicycle the same year she got her transplant.

She liked to ride a three-mile loop around the St. Joseph River, watching the birds and smell the scents in the woods. Sometimes, she’d stop and pet dogs and talk to people. Her rides were never about going fast; she was more concerned with taking in her surroundings.

When a friend told Mary Pierce about the U.S. Transplant Games, a new Olympics-style athletic event for people who’d undergone transplants, she signed up.

She remembers marching into the opening ceremonies with the other 1,000 participants, broken into groups by state. Then another large group of people entered. It became clear that these were family members of organ donors. The transplant athletes all stood and applauded.

“I wasn’t prepared for it,” she said. “There were lots of hugs and all the things that go along with meeting donor families. You can’t say thank you enough.”

Soon afterward, Mary Pierce got a call from a friend who she’d met at a support group meeting for people with alpha-1. The friend was riding in an organized bike ride for the American Lung Association. It would be three days, 60 miles a day.

“Sounds like fun,” Mary Pierce responded. “Let’s get some other alphas and make some signs, create some awareness for alpha-1 and also promote transplantation.”

She was surprised by the number of patients with lung disease who showed up with their oxygen tanks and weren’t afraid to ride their bikes, even if they could only clock half a mile.

“I wanted to encourage other lung transplant patients but particularly in the alpha-1 community to do every damn thing they could think of to keep themselves healthy and strong,” Mary Pierce said. “If a transplant failed, it wouldn’t be because they failed.”

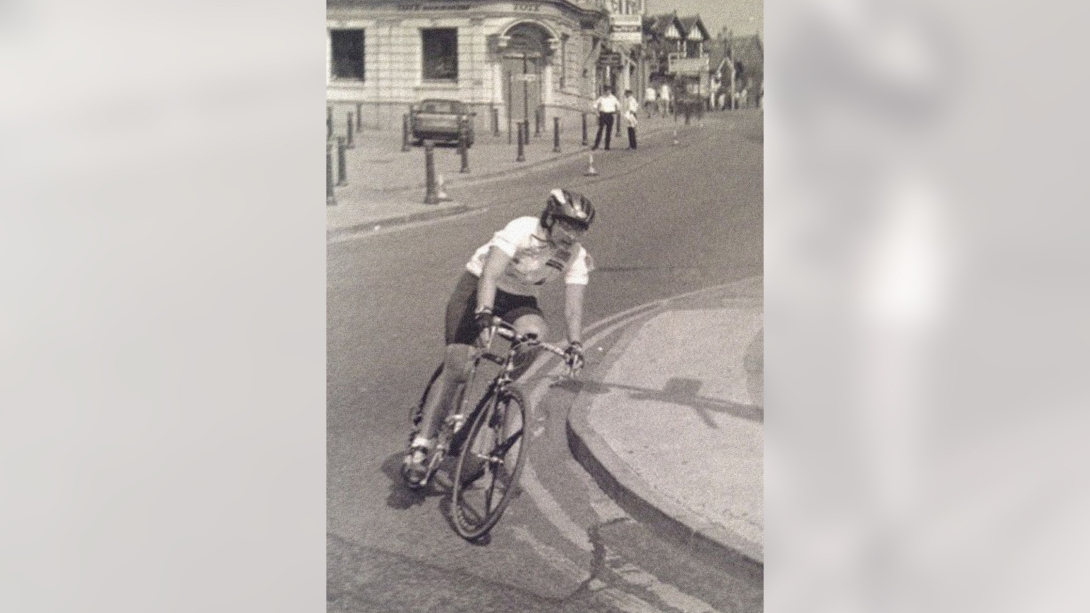

Mary Pierce at the 1995 World Transplant Games.

This became her essential mission. She organized rides across the country, partnering with the Alpha-1 Foundation to recruit more bikers and raise awareness among media outlets. In Florida, Texas, San Francisco, Colorado and New England, an array of people came out to raise awareness, ranging from healthy riders and medical providers to folks on tandem bikes with supplemental oxygen and an 80-year-old man who hadn’t ridden a bike since he was a teenager.

“I hope that when the medical teams are out there riding, they see what a patient is able to do if they’re sufficiently motivated,” she said. “It’s another example of what we can do, what we’ve got inside of us.”

Mary Pierce’s efforts peaked with the American Lung Association’s ride from Seattle to Washington, D.C., in 1998. She and 700 other riders clocked an average of 80 miles a day. She and one of her friends were the two lead media riders, so they had to be available whenever a newspaper or TV reporter wanted to talk about the ride.

“It was a great opportunity to spread the word about the American Lung Association and transplantation and alpha-1 deficiency,” she said. “It was probably the most important thing after the lung transplant that I had done.”

“She's quite a role model,” said Mohamed Wehelie, Mary Pierce’s current post-transplant coordinator at U-M Health. “We wish everybody had her drive.”

“It’s when I think of new life”

Mary Pierce continued to have an impact on the alpha-1 and lung transplant community over the next three decades, doing everything from serving as a mentor for people taking a particular treatment for alpha-1 to winning a gold medal at the World Transplant Games in Manchester, England.

She’s lived so long that she’s now contending with hip problems that have made riding her bike difficult. Wehelie says he typically has to adjust immunosuppressive medications for his patients in the first year or so after transplant, but for Mary Pierce, he’s only considering tweaking hers if she undergoes hip surgery because her meds could interfere with her healing after the operation.

“She’s been doing this for so long,” he said. “She knows what she’s doing.”

Mary Pierce has other traditionally geriatric issues to deal with, too, like the deaths of friends.

“It’s so hard because we’re a pretty close community, and we know so many people that are at risk,” she said. “Every time you get that note, you think, ‘Oh god, a missing seat at the table. A missing bike saddle.’”

The rose bush is Mary’s yard that is flourishing after being replanted.

“It’s great to see Mary Pierce and two other patients of mine who have lived for more than 20 years after their lung transplants,” Chan said, “but heartbreaking when you care for others who have passed away. It’s a perspective issue. How do we increase the number who live longer? I am at Michigan Medicine to work with our research team to achieve this goal.”

As Mary Pierce’s 30-year transplant anniversary has approached, she said she’s been thinking about a rose that she planted shortly after her surgery. It was soft pink, with lots of petals, and stretched about a foot and a half tall.

It didn’t thrive, but Todd Pierce saved the struggling flower and replanted it in a different location about two years ago. Suddenly, the rose started growing. It looked different than before. The new flower is red and has climbed about 15 feet high so far.

“You know how roses are grafted onto other rose stock?” Mary Pierce said. “The rose that I bought was gone, and the rose that came up was the old root stock. “April is the beginning of spring,” she continued. “It’s when I think of new life. The fact that the rose was dormant for all those years, and now it’s suddenly back? It feels like a parallel metaphor for my donor. My donor is there in that rose. They’ve come back.”

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!