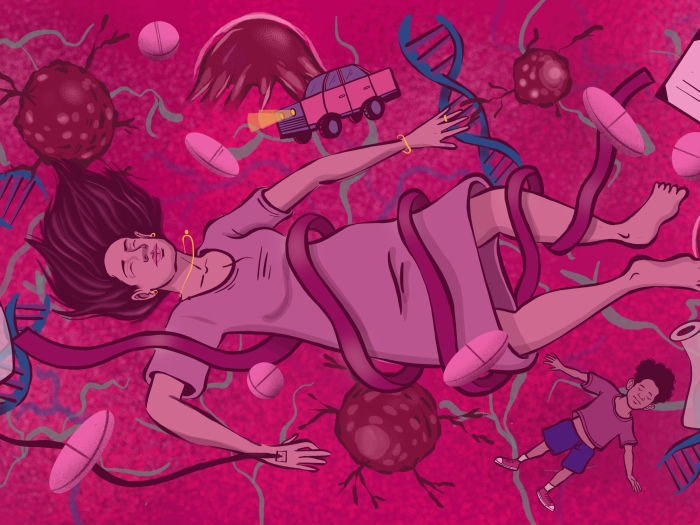

Despite living with an adenoid cystic carcinoma, Celina Pitt finds joy in nightly dance parties with her husband.

2:23 PM

Author |

Celina Pitt had reason to be frustrated.

The Michigan resident had just undergone her third surgery related to an adenoid cystic carcinoma, a rare type of glandular tumor, in her left salivary gland.

Her face and tongue were numb. She was struggling to smell and taste. Pleasure and comfort — even when interacting with Ed, her husband of more than 45 years — had become elusive.

Then Ed had an idea. He told Celina to cross her arms and wrapped his own around her to keep her stable. They swayed back and forth. They felt each other's hearts beat. For those few minutes of dancing, Celina felt better — less concerned, more relaxed, closer to the man she'd married.

"I was so scared," Celina says, "and this took away the fear."

MORE FROM MICHIGAN: Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Almost four years later, Celina and Ed still dance in their living room every night. The routine gives them a way to stay resilient and cope with challenges ranging from regaining her sense of smell to enduring a pandemic.

"I have been through hell and back," Celina says. "But I am a lot stronger than I thought I was."

How it started

Celina first experienced worrying symptoms on a trip she took to Israel and Jordan with a friend. At first, she attributed the intense pain in her jaw to a recent fall on a treadmill, assuming she'd irritated her temporomandibular joint, or TMJ, when she hit her head in the tumble.

The veteran traveler didn't let her discomfort keep her from exploring Petra's ancient streets or riding a camel through Israeli desert. But the dull ache near Celina's cheek wasn't going away, so, upon returning to the United States, she consulted her primary care physician and eventually underwent a biopsy. It revealed an adenoid cystic carcinoma, an uncommon tumor that is diagnosed in about 1,200 people nationwide each year (for comparison, about 330,000 American women are diagnosed with breast cancer annually.)

SEE ALSO: Reducing Stress for Cancer Patients During Treatment and Beyond

"I'd never even heard of such a thing," Celina says.

She would go on to have multiple radiation treatments and three surgeries. Afterward, she had to learn how to regain her sense of smell and taste. Ed devised a creative way for Celina to relearn these functions, arranging thin pieces of aromatic food such as garlic, lemons, and, her favorite, dill pickles, in attractive presentations on her plate to help her look forward to eating again.

"After surgery like that, you have to get your muscle memory back," Ed says, "For many, many weeks, we would sit at the table, turn the television off, and go through this process."

Because Celina's cancer and treatment had such an impact on her quality of life, oncologist Francis Worden, M.D., the Nancy Wiggington Oncology Research Professor of Thyroid Cancer and a professor of internal medicine at Michigan Medicine, referred her to the University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center's PsychOncology program to help manage her cancer-related anxiety. The PsychOncology staff provide education, support and counseling to address the social and psychological effects of cancer.

When Michelle Riba, M.D., M.S., a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and the director of PsychOncology, met with Celina, she discovered Celina had already implemented at least one positive coping strategy: dancing.

Riba listened as Celina detailed her nightly ritual of turning off the lights and asking Alexa to play some music. The playlist usually included one of their three favorite songs: "I Can't Help Falling in Love" by Elvis, "The Sound of Silence" (the Disturbed cover, not the Simon & Garfunkel original), and Louis Armstrong's "What a Wonderful World," which the couple first danced to at their son's wedding in 2003, well before Celina's cancer diagnosis.

"When she told me about this, it seemed brilliant," Riba says. "Dancing is fun. It brings back some memories. It's free. It combines music and activity and togetherness and love. It's simple, but really perfect."

"I think it shows resilience," she adds. "I admired them for trying to push on and keep some of their humanity."

SEE ALSO: Feeling Stressed or Down in a World with COVID? Try This Writing Tool

Celina believes she's inherited some of that determination from her parents, who were both Holocaust survivors.

Her father's train was liberated by the Russians before he arrived at Auschwitz. Mary, her mother, spent time in a different concentration camp. Once, Mary fell asleep while manufacturing ammunition for the Germans and woke up to a gun to her head. She never knew why the guard spared her. Mary would go on to live in five more countries, raise two children, and die at 90.

"You never know until something happens how you're going to handle it," Celina says. "My mother proved that she was very strong, very strong."

How it's going

Celina knows now that she, too, can persevere through the unimaginable.

Although she's angry about the injustice of her diagnosis, she remains hopeful: A recent MRI showed that the residual portion of her tumor isn't progressing. When the pandemic is over, she intends to spend time with her grandchildren again and travel to Norway to see a moose. (Yes, she's been informed that she need not go all the way to Europe to see the animal.)

And, she says, "The dancing's going to go on."

Like Podcasts? Add the Michigan Medicine News Break on iTunes, Google Podcast or anywhere you listen to podcasts.

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!