Targeting this inside-the-cell checkpoint could potentially improve response to cancer immunotherapy.

11:00 AM

Author |

It was an unexpected discovery that started with an analysis of more than 1,000 genes. The question: why game-changing cancer immunotherapy treatments work for only a fraction of patients.

The analysis shone a light on one that popped up repeatedly in patients and mouse models that did not respond to immune checkpoint therapy: stanniocalcin-1, a glycoprotein whose role in both tumors and immunology is largely unknown.

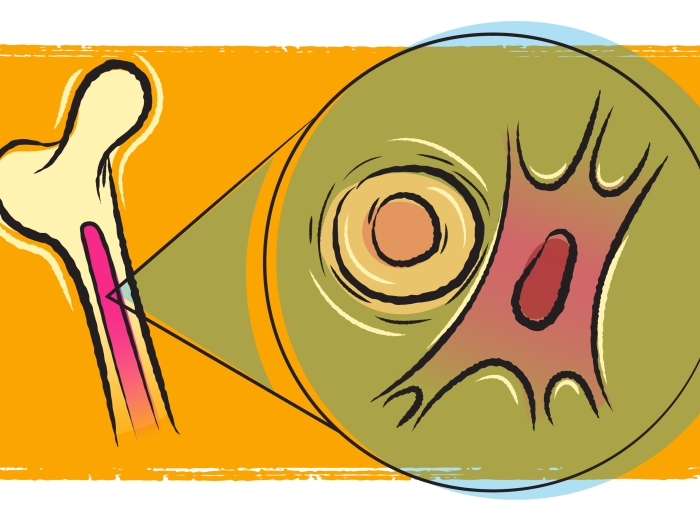

By following the trail from this surprising thread, a University of Michigan Rogel Cancer team uncovered how stanniocalcin-1, or STC1, works inside the cell to block a cellular "eat-me" signal that typically triggers the immune system to produce T cells to fight the tumor. The findings, published in Cancer Cell, provide a potential target to improve immune responses to cancer.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

"We believe STC1 is a checkpoint inside the cell. It's an eat-me blocker – it blocks macrophages and dendritic cells to eat dying or dead cancer cells. We think that if we can target the STC1 pathway, it would release the blocked eat-me signal," says study senior author Weiping Zou, M.D., Ph.D., Charles B. de Nancrede Professor of Pathology, Immunology, Biology, and Surgery at the University of Michigan.

Zou and colleagues were drawn to STC1 in part because so little was known about its role in cancer. This provided a potentially interesting opportunity, but also some difficulty as they had to start at the very beginning to understand whether STC1 was causing the poor immune response or whether it was just a bystander.

They embarked on a lengthy process, first showing that STC1 was linked with low activation of T cells and worse survival in melanoma patients treated with immunotherapy. They checked against the Cancer Genome Atlas database and found high levels of STC1 tied to worse survival in 10 different cancer types. The finding also panned out in mouse models.

SEE ALSO: New Connections Reveal How Cancer Evades the Immune System

From there, the researchers used mouse models to show that STC1 within tumors was dampening the anti-tumor T cell response by impairing the antigen presenting cells, which are essential for triggering T cells. They showed that tumor STC1 was stopping the process of macrophages, a type of antigen presenting cell, from eating dying tumor cells – a process key to presenting antigen to T cells and activating them.

Specifically, the tumor STC1 traps a key eat-me signal called calreticulin, or CRT. Without sufficient surface CRT, the macrophages won't efficiently eat the dead tumor cells. Unblock the CRT and it unblocks this process. This suggests that targeting the interaction between STC1 and CRT might be a path toward making immunotherapy more effective.

It's an unusual mechanism. Most immune checkpoint therapies are based on direct surface interactions with T cells.

"What we are talking about is before anything has happened. Before the T cells were activated, the tumors have already implemented strategies so they cannot be captured. This may be why some patients are resistant to immunotherapy: their tumors express too much STC1. When you block the eat-me signal, the antigen presenting cells cannot do their job," Zou says.

Targeting the STC1 and CRT interaction inside the cell is trickier than if it were on the cell surface. It means a typical antibody approach will not work. Instead, Zou and colleagues are investigating whether they can develop a small compound that would penetrate the cell and interfere with the STC1-CRT interaction.

Like Podcasts? Add the Michigan Medicine News Break on iTunes or anywhere you listen to podcasts.

Additional authors include Heng Lin, Ilona Kryczek, Shasha Li, Michael D. Green, Alicia Ali, Reema Hamasha, Shuang Wei, Linda Vatan, Wojciech Szeliga, Sara Grove, Xiong Li, Jing Li, Weichao Wang, Yijan Yan, Jae Eun Choi, Gaopeng Li, Yingjie Bian, Ying Xu, Jiajia Zhou, Jiali Yu, Houjun Xia, Weimin Wang, Ajjai Alva, Arul M. Chinnaiyan and Marcin Cieslik.

Funding for this work was from National Cancer Institute grants CA248430, CA217648, CA123088, CA099985, CA193136, CA152470 and P30CA46592.

Paper cited: "Stanniocalcin 1 is a phagocytosis checkpoint driving tumor immune resistance," Cancer Cell. DOI: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.12.023

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!