Researchers find an extra copy of one gene is triplicated in human Down syndrome patients, causing improper development of neurons in mice

5:00 AM

Author |

Researchers from the University of Michigan have found that an extra copy of one gene that is triplicated in human Down syndrome patients causes improper development of neurons in mice.

The gene in question, called Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule, also known as DSCAM, is also implicated in other human neurological conditions, including autism spectrum disorders, bipolar disorder and intractable epilepsy.

The cause of Down syndrome is known to be an extra copy of chromosome 21, or trisomy 21. But because this chromosome contains more than 200 genes — including DSCAM — a major challenge in Down syndrome research and treatments is determining which gene or genes on the chromosome contribute to which specific symptoms of the syndrome.

“The ideal path for treatment would be to identify the gene that causes a medical condition, and then target this gene or other genes that it works with to treat that aspect of Down syndrome,” explains Bing Ye, Ph.D., a neuroscientist at the U-M Life Sciences Institute and lead author of the study. “But for Down syndrome, we can’t just sequence patient genomes to find such genes, because we’d find at least 200 different genes that are changed. We have to dig deeper to figure out which of those genes causes which problem.”

For this work, researchers turn to animal models of Down syndrome. By studying mice that have a third copy of the mouse equivalent of chromosome 21, Ye and his team have now demonstrated how an extra copy of DSCAM contributes to neuronal dysfunction. Their findings are described in an April 20 study in PLOS Biology.

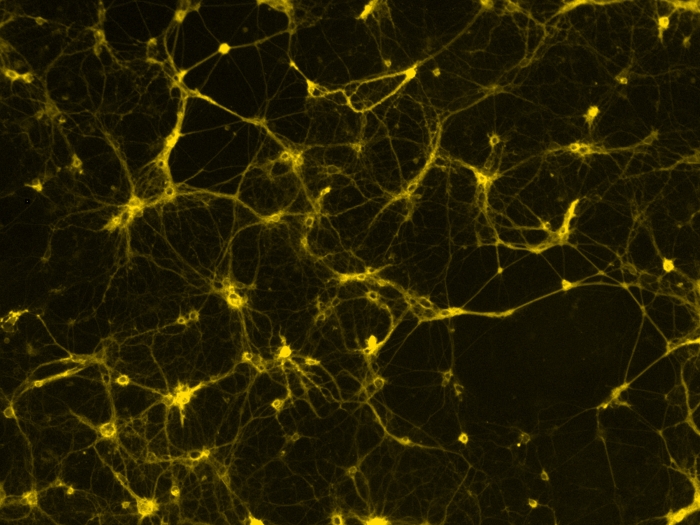

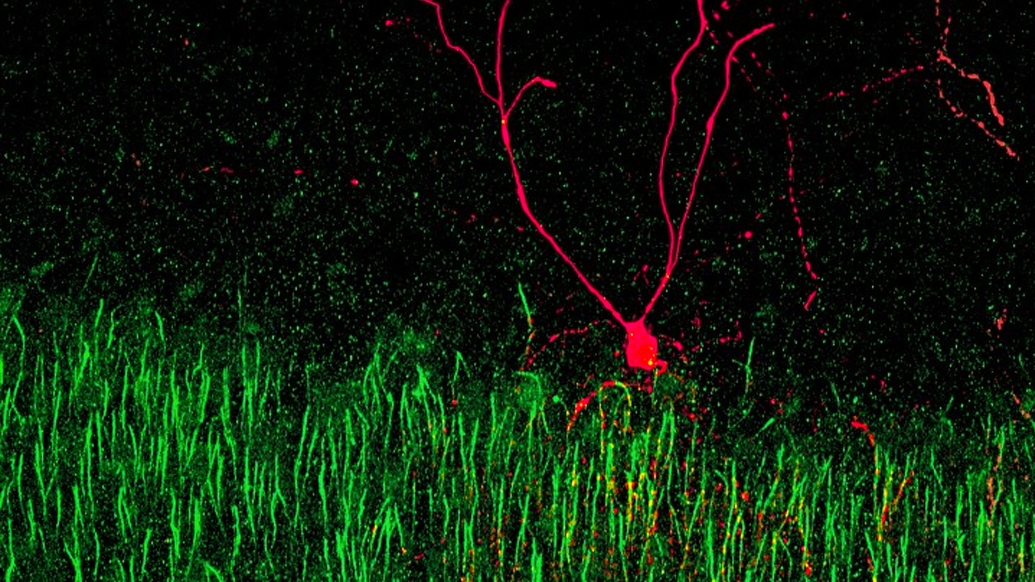

Each neuron has two sets of branches that extend out from the cell center: dendrites, which receive signals from other nerve cells, and axons, which send signals to other neurons. Ye and his colleagues previously determined that overabundance of the protein encoded by DSCAM can cause overgrowth of axons in fruit fly neurons.

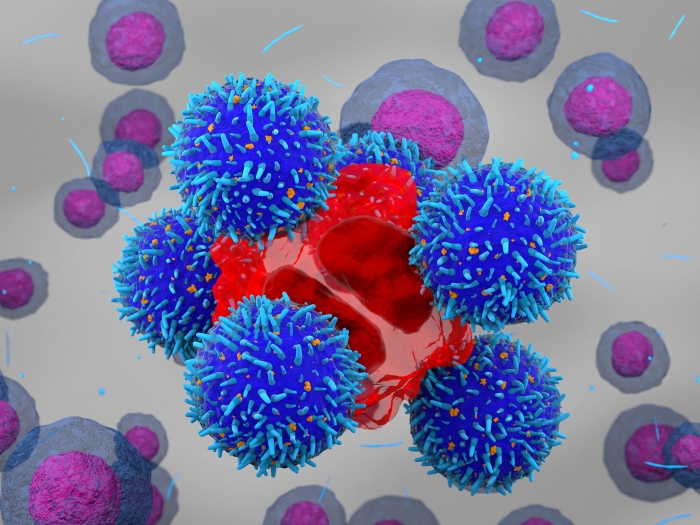

Guided by their research in flies, the team has now found that a third copy of DSCAM in mice leads to increased axon growth and neuronal connections (called synapses) in the types of neurons that put the brakes on other neurons’ activities. These changes lead to greater inhibition of other neurons in the cerebral cortex — a part of the brain that is involved in sensation, cognition and behavior.

“It's known that these inhibitory synapses are changed in Down syndrome mouse models, but the gene that underlies this change is unknown,” says Ye, who is also a professor of cell and developmental biology in the U-M Medical School. “We show here that the extra copy of DSCAM is the primary cause of the excessive inhibitory synapses in the cerebral cortex.”

The team demonstrated that in mice that had only two copies of DSCAM, but three copies of the other genes that are similar to human chromosome 21 genes, axon growth appeared normal.

“These results are striking because, although these mice have an extra copy of about a hundred genes, normalization of this single gene, DSCAM, rescues normal inhibitory synaptic function,” explains Paul Jenkins, Ph.D., an assistant professor of pharmacology and psychiatry at the Medical School and co-corresponding author of this study.

“This suggests that modulation of DSCAM expression levels could be a viable therapeutic strategy for repairing synaptic deficits seen in Down syndrome," Jenkins adds. "In addition, given that alterations of DSCAM levels are associated with other brain disorders like autism spectrum disorder and bipolar disorder, these results shed insight into potential mechanisms underlying other human diseases.”

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Brain Research Foundation, and the University of Michigan.

Study authors are: Hao Liu, René N. Caballero-Florán, Ty Hergenreder, Tao Yang, Jacob M. Hull, Geng Pan, Ruonan Li, Macy W. Veling, Lori L. Isom, Kenneth Y. Kwan, Paul M. Jenkins, and Bing Ye of the University of Michigan; Z. Josh Huang of Duke University; and Peter G. Fuerst of the University of Idaho.

Paper cited: “DSCAM gene triplication causes excessive GABAergic synapses in the neocortex in Down syndrome mouse models,” PLOS Biology. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3002078

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!