What to know about the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest infection alert

12:35 PM

Author |

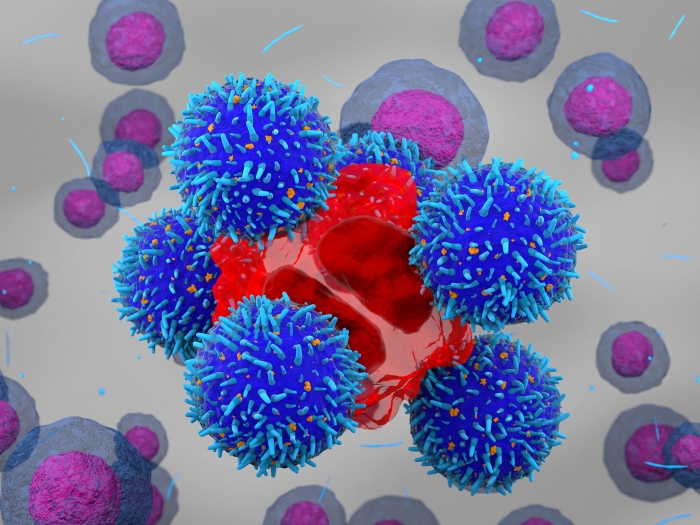

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued an alert that infections from the fungus Candida auris are increasing. Teresa O’Meara, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Microbiology & Immunology at the U-M Medical School, speaks about the emerging threat.

Where did Candida auris come from?

O'Meara: We don’t have data on where this fungus came from in the environment. It was first isolated in 2009 and has been causing outbreaks in hospitals and other healthcare facilities since then. In some areas, it’s endemic, which means it’s consistently present but limited to a particular community, and has been found on fruit and animals, for example.

What is potentially happening is that as patients are being moved from hospital to hospital, they can introduce Candida auris into the environment. There, the fungus is very resistant to mitigation and spreads in the hospital across patients.

One of the big risk factors researchers have discovered are ventilator-associated infections in nursing facilities—and those have been in heavy use recently due to the pandemic.

Who is at greatest risk of infection from Candida auris?

O'Meara: The medically vulnerable, mostly patients in hospitals. These individuals often have catheters, ports and other interventions that increase the risk of introducing the fungus to the bloodstream.

And while C. auris is not a threat to healthy individuals, the problem is that if you are carrying the fungus around on your body, for instance, you can transmit it to a medically vulnerable person. It’s very hard to get off skin; the decontamination efforts are pretty tricky.

One of the hypotheses is that the fungus gets into the hair follicles, meaning that even if you are using antiseptics or disinfectants, it can persist in this reservoir where its protected.

How big a threat is C. auris to the public?

O'Meara: There aren’t that many cases in the United States compared to other fungal pathogens that are really damaging, but there are an increasing number of patients with it, which means more people colonized and more potential for worse outcomes.

Let’s put it into context: Candida albicans, another fungus I work on, is currently colonizing 20-80% of people. This is a common fungus that causes yeast infections, but also causes thousands of serious bloodstream infections a year.

We have orders of magnitude fewer cases for Candida auris, but the fungus is a really big problem for infection control. I think people are trying to figure out the best strategies for infection control and prevention in hospitals now that it’s becoming more prevalent.

Is it a fungus for which normal tools aren’t as effective?

O'Meara: Yes. I think people are thinking about it the way we think about the bacteria C. difficile in hospitals. You must have specific infection control procedures in place to prevent C. diff. My understanding is that similar kinds of strategies would need to be put in place to prevent spread of Candida auris among patients in hospitals.

What is it about C. auris that makes it tough to get rid of?

O'Meara: It seems to be resistant to the quaternary ammonium cleaners used in hospitals. It’s not resistant to bleach, which is often not used because it can damage medical equipment. The fact that it is very persistent also plays a role. There have been studies that show when you allow it to dry on a surface, it can last for weeks.

What is your lab researching about C. auris?

O'Meara: One of the big projects in my lab is figuring out why C. auris is so sticky and why it can attach to surfaces and resist decontamination efforts. We’re also trying to figure out the differences between strains of C. auris and whether there are specific outbreak causing strains. We want to know whether there are variants that are more infectious, persistent, or transmissible and try to nail down the genetic components that cause that variability.

Other researchers are trying to determine why some strains of C. auris are drug resistant and how they can accumulate resistance mutations without losing any fitness, or ability to multiply.

What tools can be used to prevent further cases of C. auris?

O'Meara: All we have right now is infection prevention: making sure potentially contaminated equipment isn’t moved from patient room to patient room, getting better decontamination procedures in place, figuring out decontamination protocols for different strains, figuring out the places C. auris can hide and where we need to be sampling. Another important step is figuring out how to identify patients that are colonized and whether we can do more screening upon patient entry to a hospital.

What questions will basic science help with?

O'Meara: Hopefully, we can figure out how C. auris adheres to different surfaces and whether we can develop vaccines against colonization.

The fact that C. auris is not as dangerous as C. albicans is also interesting scientifically: how is it avoiding causing disease while in the bloodstream?

The threat from C. auris is similar to the threat from MRSA, but we know less about fungal infections than we do about bacterial infections because fungi are an underfunded, understudied set of organisms. There’s a lot of work to be done.

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!